[T]he Christian story is precisely the story of one grand miracle, the Christian assertion being that what is beyond all space and time, what is uncreated, eternal, came into nature, into human nature, descended into His own universe, and rose again, bringing nature with Him. It is precisely one great miracle. If you take that away there is nothing specifically Christian left. [...] Conversely, once you have accepted that, then you will see that all other well-established Christian miracles [...] are part of it, that they all either prepare for, or exhibit, or result from the Incarnation.

~C.S. Lewis, in "The Grand Miracle", from God in the Dock

The central miracle asserted by Christians is the Incarnation. They say that God became Man. Every other miracle prepares for this, or exhibits this, or results from this. [...] What can be meant by 'God becoming man'? In what sense is it conceivable that the eternal self-existent Spirit, basic Fact-hood, should be so combined with a natural human organism as to make one person?

We tend to gloss over the miracle that is Christmas, fixating instead on the miracle of Easter, or even Christ's miracles of healing and provision while on earth. Christmas doesn't seem that big a deal, theologically. A baby was born to virgin, but we aren't really sure why it matters. After all, he doesn't really do much until he's a grown man. It's his death that matters most, right? And his subsequent resurrection? Heck, the early church didn't even celebrate Christmas as a distinct holiday--not for a couple hundred years, anyway. They celebrated the resurrection by meeting every Sunday, but there's no mention of observing Christmas (or Easter, for that matter--at least not as an annual thing--and because of its connection to Passover, we actually know when Easter was). And the Puritans weren't big on Christmas at all; they rebelled against it as a Catholic invention and claimed it was infested with pagan elements and lacked any biblical justification.~C.S. Lewis, in "The Grand Miracle", from Miracles

|

| "The virgin will be with child and will give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel", which means "God with us." ~Matthew 1:23 |

Yet Lewis says that the miracle of Christmas is the central miracle of the Bible--and I have to agree. After all, as I think Lewis points out somewhere (though I can't for the life of me remember where), once you grant that God is made Man, the rest of the gospel story falls into place. If Christ is the God-Man, then of course He is able to live a sinless life. Of course he has the power to heal, to calm storms and cast out demons. And if that God-Man dies, of course his death has different repercussions than a normal human death--it makes sense that it would accomplish something stupendous and unique, that it would atone for the sins of others. Of course death does not affect him in the same way it affects us, so of course he does not stay dead. All of that makes sense once you accept Christ as the miraculous God-Man.

Granted, it's a big miracle to accept. We forget that sometimes. We think being born of a virgin is a miracle on par with walking on water or healing the blind or multiplying meager provisions. And yeah, the God who can do all those things could stick a baby in a virgin womb without batting an eye. But the nature of the baby is a miracle on an altogether different scale. Fully God, yet fully man? How is that even possible? As Lewis notes, 'In what sense is it conceivable that the eternal self-existent Spirit, basic Fact-hood, should be so combined with a natural human organism as to make one person?'

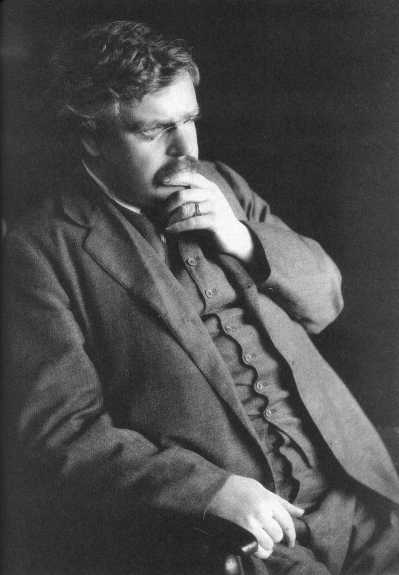

G.K. Chesterton makes the following observation about the laws of fairyland:

[Learned men in spectacles] talked as if the fact that trees

bear fruit were just as necessary as the fact that two and one trees make three. But it is not. There is an enormous difference by the test of fairyland; which is the test of imagination. You cannot imagine two and one not making three. But you can easily imagine trees not growing fruit; you can imagine them growing golden candlesticks or tigers hanging on by the tail. These men in spectacles spoke of a man named Newton, who was hit by an apple, and who discovered a law. [...] But we can quite well conceive the apple not falling on his nose; we can fancy it flying ardently through the air to hit some other nose, of which it had more definite dislike. [...] we believe in bodily miracles, but not in mental impossibilities. We believe that a Bean-stalk climbed up to Heaven; but that does not at all confuse our convictions on the philosophical question of how many beans make five. ~G.K. Chesterton, in "The Ethics of Elfland", from Orthodoxy

It seems to me that this fits rather nicely with a discussion of miracles. Most of the miracles of Christianity fall into the 'fairyland' category--things we can imagine. We can imagine the Red Sea parting, the walls of Jericho crumbling. We can imagine water gushing from a rock, or manna falling from heaven. We can imagine birds feeding a prophet, or a jug of oil that never runs dry. We can imagine the blind seeing, the lame walking, the dead being raised. Water turning to wine, bread and fish multiplied . . . these are all within the realm of human imagination. They are analogous to Chesterton's beanstalk to heaven. They don't happen much, but we can imagine them.

The Incarnation, though, strikes me more as a 'how many beans make five' sort of miracle. We simply cannot get our brains around it. It is like being told that two trees and one tree make four trees (and without some sort of clever riddle being involved). Two natures, one person. God, man. Infinite, finite. A and not A. It just does not compute. We only know about it because we are told the mere fact of it in Scripture. And even then, it's not really explained. The sum total of our knowledge is that Jesus is both 'A' : God and 'not A' : Man. That's it. We don't know what that really looks like, or how it works. It doesn't make a lick of sense to our human brains. But we see the fact of it in Scripture, and by the grace of God, we believe it. And once we do, the other pieces of the salvation story fall into place.

I guess it's like the song says: Christmas really is the most wonder-full time of the year.

No comments:

Post a Comment